Viable ectopic pregnancy with hemoperitoneum

Obiozor A.A MBBS, FWACS,1 Obiozor C.G2

Abstract

Pregnancy is said to be ectopic when it occurs outside the uterus, most commonly in the fallopian tube. There is high index of suspicion when a pregnant woman experiences any of these symptoms in the first trimester: vaginal bleeding, lower abdominal pain, and amenorrhea. An elevated BhCG level above (2000 mIU/ml) with an empty uterus on a transvaginal ultrasound is necessary for confirming ectopic pregnancy diagnosis. Ectopic pregnancy can be managed medically with methotrexate or surgically via laparoscopy or laparotomy depending on the hemodynamic stability of the patient and the size of the ectopic mass.

We present a case of a left-sided viable ectopic pregnancy with massive hemoperitoneum in a 31-year-old primigravid female, who presented to a peripheral radiological centre in Umuahia Abia state with history of amenorrhea for two months severe abdominal pain and signs of hypovolemic shock. The patient was scanned trans-abdominally and findings revealed an empty uterine cavity and a live 11 weeks fetus (measured by CRL), The fetus was seen within a gestational sac in the left side of the abdominal cavity floating in a free fluid in keeping with ruptured tubal ectopic pregnancy of 11wks duration. The patient underwent urgent exploratory laparotomy which revealed a ruptured left tubal ectopic pregnancy with significant intra-abdominal haemorrhage. Surgical intervention was successfully performed, culminating in the removal of the ectopic pregnancy, salpingectomy and hemostasis of the bleeding vessels. The patient recovered well postoperatively and was discharged with appropriate follow-up care. This case highlights the importance of early recognition, radiological evaluation and prompt management of ectopic pregnancies to prevent life-threatening complications.

Keywords: Ectopic Pregnancy, Hemoperitoneum, Laparotomy, Salpingectomy, Hypovolemic Shock

Introduction

Ectopic pregnancy occurs when a developing blastocyst implants outside the endometrial cavity1, although it is rare 1.3% to 2.4% of all pregnancies2 , it can result in significant morbidity and mortality if not promptly diagnosed and managed. About 90% of ectopic pregnancies occur in the fallopian tubes, while the rest implants on the cervix, the ovary, the myometrium and other sides3. Ectopic pregnancy is diagnosed with ultrasound finding of extrauterine gestation and positive serological confirmation of pregnancy4. We present a case of a left-sided viable ectopic pregnancy with massive hemoperitoneum, a rare and challenging presentation that necessitated urgent surgical intervention.

Case presentation:

A 31-year-old Nigerian female presented to a peripheral radiological centre in Umuahia, Abia state with sudden-onset of severe left lower quadrant abdominal pain, amenorrhea and dizziness. Upon examination, she was tachycardic, hypotensive, and had signs of peritoneal irritation. Laboratory investigations revealed a falling hemoglobin level suggestive of significant blood loss. Beta human Chorionic Gonadotrophin (ß-hCG) level was above 112000IU. Emergency ultrasound demonstrated a left tubal ectopic pregnancy with evidence of hemoperitoneum.

Figure 1: Abdominal ultrasound showing intraperitoneal haemorrhage

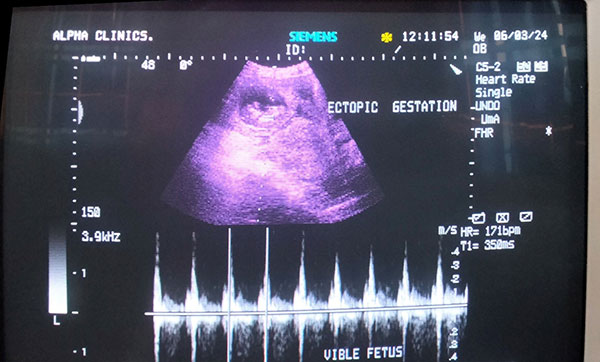

Figure 2: Showing ectopic viable gestation

Management:

The patient was resuscitated with intravenous fluids and blood transfusions and taken emergently to the operating room for exploratory laparotomy. Intraoperatively, a ruptured left tubal ectopic pregnancy was identified as the source of massive hemoperitoneum. The ectopic pregnancy was excised, salpingectomy done and hemostasis was achieved successfully.

Outcome:

The patient recovered well postoperatively and was monitored closely for any signs of complications. She was discharged with appropriate instructions for follow-up care and contraception counseling to prevent future ectopic pregnancies.

Discussion:

Left-sided viable ectopic pregnancies with massive hemoperitoneum are rare but can lead to life-threatening complications if not managed promptly. Ectopic pregnancy is a well-known cause of first trimester pregnancy complication and maternal mortality, it is responsible for 9% to 13% of all pregnancy-related deaths2. Majority of ectopic pregnancies implant at different locations in the fallopian tube, most commonly in the ampulla (70%), followed by the isthmus (12%), fimbria (11.1%), and interstitium (2.4%)5. Tubal pregnancy usually becomes symptomatic in the first trimester due to the lack of submucosal layer within the fallopian tube wall which enables occyte implantation within the muscular wall, allowing the rapidly proliferating trophoblasts to erode the muscularis layer. This often causes tubal rapture at 7.2 weeks ± 2.2, leading to hemorrhage and shock5. However, cases of advanced gestational age with different presentations have been reported in the literature. Such events are rare as it is unusual for the fallopian tube to dilate to the point of accommodating a second- or third-trimester fetus5. Biochemical investigation (BhCG) and skilled sonographic evaluation of the pelvis in a patient with a suspected ectopic pregnancy play a vital role in accelerating the management of patients6.

This case underscores the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for ectopic pregnancies in women of reproductive age presenting with abdominal pain, amenorrhoea and hemodynamic instability. Early diagnosis, resuscitation, and prompt surgical intervention are crucial to achieving good outcomes for patients with this condition.

Conclusion:

This case report highlights the successful management of a left-sided viable ectopic pregnancy with massive hemoperitoneum through timely surgical intervention. Clinicians should remain vigilant for ectopic pregnancies in women of reproductive age presenting with acute abdominal pain, amenorrhoea and hemodynamic instability to prevent adverse outcomes.

References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 191: Tubal ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:0. [Google Scholar]

- Taran FA, Kagan KO, Hübner M, Hoopmann M, Wallwiener D, Brucker S. The diagnosis and treatment of ectopic pregnancy. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:693–704. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panelli DM, Phillips CH, Brady PC. Incidence, diagnosis and management of tubal and nontubal ectopic pregnancies: a review. Fertil Res Pract. 2015;1:15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belics Z, Gérecz B, Csákány MG. Early diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. Orv Hetil. 2014;155:1158–1166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil MM, Shazly SM, Badran EY. An advanced second trimester tubal pregnancy: case report. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2012;17:136–138. [Google Scholar]

- Santos L, Oliveira S, Rocha L, et al. Interstitial pregnancy: case report of atypical ectopic pregnancy. Cureus. 2020;12:0. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]