Macula Lesions in Retinitis Pigmentosa

Babalola YO1,2, Adebusoye SO2

Abstract

Aim: To describe the pattern of macula lesions in patients with retinitis pigmentosa attending a Retina outpatient clinic in Ibadan, Nigeria.

Methodology: A retrospective review of patients with retinitis pigmentosa seen at the Retina clinic of the University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria between May 2018 and June 2022. Data analysis was by SPSS (version 23) and statistical significance was placed at p < 0.05

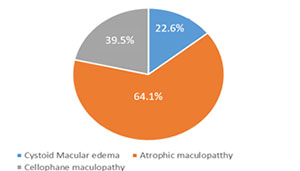

Results: Forty-six (2.4%) of 1911 patients seen at the retina clinic during the study period had a diagnosis of retinitis pigmentosa. There were 24 (55.8%) males and 19 (44.2%) females. The mean age was 39.4 ± 19.2 years (range of 9 to 78 years). Eighty-six percent of patients were of the Yoruba ethnic group. The most common ocular complaint was poor vision which was present in forty patients (93.0%), followed by poor night vision in 26 (74.3%) patients and loss of peripheral vision in 11 (47.8%) patients. Visual impairment was present in 72.2% of patients. Maculopathy accounted for 61.3 percent of patients with visual impairment. Fifty-three (68.9%) eyes had macula lesions. This accounted for 62. 8% of all patients with RP. The macula lesions include atrophic maculopathy, cystoid macula oedema and epiretinal membrane. Atrophic maculopathy was the most common maculopathy. Coexisting ocular morbidities such as cataract dominantly of the posterior subcapsular morphology was present in 33 (42.3%) eyes while glaucoma was present in two eyes of a single patient.

Conclusion: Macula lesions in retinitis pigmentosa may be a main cause of visual impairment in this population. Atrophic maculopathy is the most prevalent macula lesion associated with RP in this study.

Keywords: Atrophic maculopathy, Cystoid macula oedema, Epiretinal membrane, Nyctalopia, Ocular comorbidities, Visual impairment

Introduction

Retinitis pigmentosa is a common hereditary retinal disease.1 It is typically described as a rod- cone dystrophy as the photoreceptors more commonly affected are the rods.2 Clinical presentation of affected patients include nyctalopia, blurred vision, difficulty with peripheral vision, floaters and bumping into objects.3,4 Visual impairment is a sequel of RP.5 In part, macula lesions may be a contributing factor to visual impairment in patients with RP.6 Prevalent macula lesions or maculopathy associated with RP include cystoid macula oedema, epiretinal membrane (cellophane maculopathy) and atrophic maculopathy.4-7 Cystoid macula oedema is thought to be the most common maculopathy associated with RP though recent studies in diverse populations highlighted other maculopathies as predominant.4,8,9 Typically, macula lesions in any form usually have an effect on central vison, hence this study focuses on the macula lesions and visual impairment in patients with RP.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective study of all consecutive patients diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa at the retina clinic of the University College Hospital, Ibadan between May 2018 and June 2022. The demographic data, best corrected visual acuity, presenting complaints and ocular examination findings were retrieved from patients’ notes. Statistical analysis was done with SPSS Version 23. The diagnosis of RP was made from the clinical history, dilated binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy and slit lamp biomicroscopy with +78 D lens.

Clinical notes of all patients with a clinical diagnosis of retinitis pigmentosa over a four year period (May 2018 to June 2022) at the vitreoretinal unit of the University College Hospital, Ibadan were retrieved. The gender, age, presenting symptoms, family history/pedigree were noted. Optical coherence tomography scan and fundus photography had been done for a few of the patients. Electroretinography and genetic molecular studies was not available locally. Assessment of the mode of inheritance was based on pedigree.

A patient was classifed as autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa if there was a history of the disease in the patient’s parents, uncle, and or siblings; autosomal recessive inheritance if the patient was the only one affected in the family and there was a history of the disease among cousins of both parents. X-linked inheritance was documented if the patient’s brother or grandfather had the disease but there was no clinical disease in the parents. In the absence of a clear history suggestive of inheritance, the disease was regarded as simplex pattern. The Descriptive Statistics (cross tabulation) was calculated for different clinical entities. The best-corrected distance visual acuity was recorded. The best-corrected monocular visual acuity obtained from each patient was used in the analysis.

Results

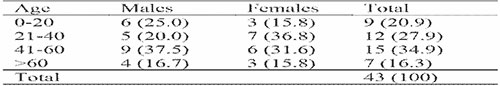

Forty-six (2.4%) of all the 1,911 new patients seen in the vitreo-retina unit during the study period had RP. The patient notes of 43 patients were available and analyzed. There were 24 (55.8%) males and 19 (44.2%) females with a male: female ratio of 1.3:1. The age range of the patients was 9 to 78 years with a mean age of 39.4 ± 19.2 years. (Table 1) A large proportion of the patients (34.9 %) were between 41-60 years of age. Majority of the patients (86.0%) were of Yoruba ethnicity.

Table 1: Age distribution of patients with retinitis pigmentosa

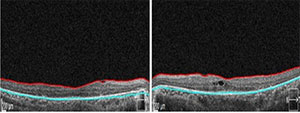

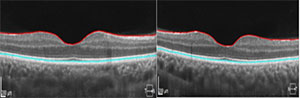

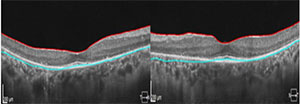

All the patients analyzed had bilateral disease. The diagnosis of RP was made in one eye in a single patient with a diagnosis of vitreous haemorrhage secondary to proliferative sickle cell retinopathy in the other eye which precluded a view of the fundal details. 62.8 % of the patients with RP had macula lesions. Fifty-three (68.9%) eyes had macula lesions of which atrophic maculopathy was the most common. (Figures 1, 2, 4 and 5). The remaining eyes had normal foveal architecture. (Figure 3) Maculopathy was the cause of visual impairment in 19 (61.3%) of the patients. The predominant complaints were poor vision (93.0%), night blindness (74.3%), and peripheral vision (47.8%). The median time to presentation from the onset of symptoms was 8 years (IQR=4-20 years).

Figure 1: Fundus photographs of a 46-year old man with retinitis pigmentosa showing bone spicule pigmentation, arteriolar attenuation and atrophic maculopathy

Figure 2: Optical coherence tomography of a 52-year old man with retinitis pigmentosa showing atrophic macula changes in both eyes and left cystoid macula oedema

Figure 3: Optical coherence tomography of a 28-year old woman with retinitis pigmentosa showing normal fovea

Figure 4: Optical coherence tomography of a 31-year old woman with retinitis pigmentosa showing early atrophic changes at the macula

Figure 5: Distribution and types of maculopathy in patients with retinitis pigmentosa

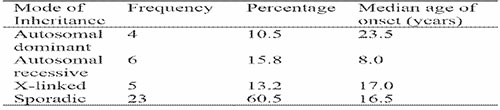

From the information retrieved from the patient notes, 39 (90.7%) patients were probed for a family history/pedigree for RP. From this, autosomal dominant inheritance was suggestive in 7 (18.4%) patients, autosomal recessive inheritance in 3 (7.9%) patients, and X-linked inheritance 5 (13.2%) patients. The clinical history was non-specific of the mode of inheritance in 23 (60.5%) patients, and these were regarded as simplex case. (Table 2) Two of the four patients presumed to have sporadic sporadic disease also had hearing loss co-existing with ophthalmic features of RP and consistent with Usher syndrome. A single patient with features of polydactyl, obesity, and fundal features of RP was suggestive of Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Syndromic retinitis pigmentosa was present in three (7.9%) of the patients’ included in the study.

Table 2: Mode of inheritance

Macula lesions accounted for visual impairment in 61.3% of participants. 27.5% of the respondents had improvement from their presenting VA by 2 or more Snellen lines with refraction. 18 (45.0%) had no improvement from their presenting VA. (Table 3) Intra ocular pressures were normal in all but one subject; the exception was the only patient with co-existing glaucoma and had IOP of 25mmHg in both eyes. Thirty-three (42.3%) eyes from 17 persons had cataract and posterior subcapsular cataract was the commonest morphology present in 21.8% of the patients. Unexpectedly, glaucoma was seen in a single patient.

Table 3: Visual acuity patients with retinitis pigmentosa

Discussion

Macula lesions are well-known associations of RP and may be the aetiology of visual impairment.5,7,8 Earlier studies have shown that atrophic maculopathy was the most common type of macula lesion in RP as seen in our index study.8 A more recent study in which optical coherence tomography scanning was utilized revealed epiretinal membrane and cystoid macula oedema (CMO) respectively as the most common macula lesions.4,7 These findings were in an Asian populations in comparison to our African population. Sixty-two point eight percent of our patients had macula lesions and was higher than the prevalence from a multicenter study in South- West Nigeria with a prevalence of 36.5% but similar to a cohort in China in which 59.7% had macula involvement.3,4

The prevalence of macula lesions in this study varied widely from a study in Onitsha in which only 1 patient (2.7%) was diagnosed with maculopathy.9 Unlike our study which had atrophic maculopathy as the commonest macula pathology, cystoid macula oedema was the commonest lesion in the multicenter population in Nigeria.3 Epiretinal membrane(ERM) closely followed cystoid macula oedema as the prevalent lesions in an Italian population and comparable to this study in which ERM was the second most prevalent lesion.10

There was a higher prevalence 72.2% of visual impairment in comparison to a study in the United States in which the prevalence of visual impairment was 12% and 8% respectively.5,11 In both of these studies, large populations of patients with retinitis pigmentosa were evaluated in comparison to our study. Poor vision was the commonest presenting symptoms in most patients just as found in various studies.3,9,12

Optical coherence tomography scan is the gold standard in diagnosis of macula lesions. In our environment due to cost and financial constraints, most of the patients did not have an OCT scan done hence, diagnosis was clinical and based on the characteristic feature of the various macular lesions. Our findings differed from studies utilizing OCT found that cystoid macula oedema was the most frequent macula lesion.7,10 Similar to our findings, atrophic maculopathy was the most common finding accounting for 38.2% of lesions in a local study which utilized OCT scans for diagnosis.12,13 The second most frequent lesion in the population studied was cystoid macula oedema which was in variation to our finding of epiretinal membrane.12

Cataract was the commonest ocular comorbidity and glaucoma was uncommon which is similar to the findings in Onitsha, Nigeria.9 Myopia was also the most common refractive error as seen in another study and is expected as it is a known ocular associations of RP.3,4,12 Atrophic maculopathy was found to be twice as prevalent in black patients in contrast to Caucasian patients in the United States. These may explain the high prevalence of atrophic maculopathy in our patients who were all Nigerian and of African origin.12,14

Conclusion

Atrophic maculopathy was the commonest macula lesion in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Macula lesions are responsible for visual impairment in a significant number of these patients. Optical coherence tomography scan may aid accurate diagnosis of these maculopathies when available. It is recommended that all patients with retinitis pigmentosa should have detailed macular examinations and optical coherence tomography scanning at diagnosis if available. Regular follow-up should be mandatory for prompt diagnosis of macula lesions in RP as it is a major cause of visual impairment in these patients.

References

- Hamel C. Retinitis pigmentosa. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:40.

- Ferrari S, Di Iorio E, Barbaro V, Ponzin D, Sorrentino FS, Parmeggiani P. Retinitis Pigmentosa: Genes and Disease Mechanisms. Curr Genomics. 2011 Jun; 12(4): 238–249.

- Onakpoya OH, Adeoti CO, Oluleye TS, Ajayi IA, Majengbasan T, Olorundare OK, et al. Clinical presentation and visual status of retinitis pigmentosa patients: a multicenter study in southwestern Nigeria. Clin Ophthalmol.2016;10:1579-83.

- Tan L, Long Y, Li Z, Ying X, Ren J, Sun C, et al. Ocular abnormalities in a large patient cohort with retinitis pigmentosa in Western China. BMC Ophthalmol. 2021; 21:43.

- Vezinaw CM, Fishman GA, McAnany JJ. Visual impairment in retinitis pigmentosa. Retina. 2020 Aug;40(8):1630-1633.

- Liew G, Moore AT, Bradley PD, Webster AR, Michaelides M. Factors associated with visual acuity in patients with cystoid macular oedema and Retinitis Pigmentosa. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2018 Jun;25(3):183-186.

- Hagiwara A, Yamamoto S, Ogata K, Sugawara T, Hiramatsu A, Shibata M, et al. Macular abnormalities in patients with retinitis pigmentosa: prevalence on OCT examination and outcomes of vitreoretinal surgery. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011 Mar;89(2):e122-5.

- Fishman GA, Fishman M, Maggiano J. Macular lesions associated with retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol 1977. 95(5): 798–803.

- Nwosu SNN, Ndulue CU, Ndulue OI, Uba-Obiano CU. Retinitis Pigmentosa in Onitsha, Nigeria. J West Afr Coll Surg. 2020 Apr-Jun;10(2):30-35.

- Testa F, Rossi S, Colucci R, Gallo B, Di Iorio V, della Corte M, et al. Macular abnormalities in Italian patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014 Jul;98(7):946-50.

- Grover S, Fishman GA, Alexander KR, Anderson RJ, Derlacki DJ. Visual Acuity Impairment in Patients with Retinitis Pigmentosa. Ophthalmology 1996. 103(10), 1593–1600.

- Okonkwo ON, Hassan, AO. Agweye CT, Umeh V, Akanbi T. Clinical Presentation and Macular Morphology in Retinitis Pigmentosa Patients. Annals of African Medicine 2023. 22(4):451-455.

- Babalola YO, Baiyeroju AM. Optic disc drusen and a constellation of other features of Retinitis pigmentosa: A Case report. International Journal of Ophthalmology & Visual Science. Int J Ophthal & Vis Sci 2021;(6) 1:63-66.

- Fishman GA, Lam BL, Anderson RJ. Racial differences in the prevalence of atrophic-appearing macular lesions between black and white patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994. 15;118(1):33-8.