A seven-year review of emergency peripartum hysterectomy in a tertiary hospital in northern Nigeria

Shittu MA, Olaoye SO, Fasanu OT

Abstract

Background: Emergency peripartum hysterectomy (EPH) is surgical removal of the uterus during childbirth or within its immediate 24 hours, a lifesaving procedure done as the last resort to control obstetric haemorrhage.

Objectives: To determine the incidence, indications, and complications of peripartum hysterectomy.

Methods: The study is a retrospective review of emergency peripartum hysterectomies performed at the Centre from 1st January, 2015 to 31st December, 2021. The patients’ case folders were retrieved from the medical records department and relevant information obtained using a structured data extraction format. The data was analyzed using SPSS version 26. Means, frequency, and percentages were used to present the significance of the results.

Results: A total of 46 EPH were performed between January 2015 and December 2021 out of 20,832 deliveries within the same period, giving an incidence of 0.22% (2.2 per thousand deliveries). Indications were uterine rupture (78.2%), uterine atony (10.9%), abruptio placentae (4.3%), placenta previa (4.3%) and placenta accreta spectrum (2.2%). Subtotal hysterectomy was performed in most cases (39/46; 84.8%). The most common complication was intraoperative haemorrhage requiring blood transfusion (100%). Other complications included severe post-operative anaemia, wound sepsis, paralytic ileus and enterocutaneous fistula. The maternal case fatality was 4 (8.7%) and all the mortality cases were unbooked patients.

Conclusion: The incidence of emergency peripartum hysterectomy is relatively low in our study and uterine rupture is the most common indication. EPH is associated with significant maternal morbidity and mortality, and this is related to booking status. Hence, enlightening women on antenatal care and hospital delivery will help in reducing maternal morbidity and mortality.

Keywords: Emergency peripartum hysterectomy, uterine rupture, subtotal hysterectomy

Introduction

Peripartum hysterectomy is the surgical removal of the uterus during pregnancy or postpartum, it is a life-saving procedure performed as a last resort to control serious obstetric haemorrhage.1 Emergency peripartum hysterectomy has been defined as hysterectomy performed at the time of child birth or within 24 hours of child birth or at any time from childbirth to discharge from the same hospitalization.2

It is not a very commonly performed procedure, studies have put the incidence world-wide to range between 0.035% to 0.54%.3-7 In Nigeria, the incidence is 0.2% to 0.62% (2 to 6.2 per 1000 deliveries).6,8 Though the incidence of peripartum hysterectomy tends to have been increasing in both developed and developing countries, it is higher in developing countries.9 The growing rates of caesarean births and the resultant rise in placenta previa and placenta accreta spectrum, particularly in high-income nation and factors such as poor transportation to suitable medical facilities, unavailable modern obstetric services such as uterine artery embolization, false religious and cultural beliefs, poverty, poor uptake of family planning services and inadequately monitored births in developing countries have all contributed to this increase.6,7,10

Peripartum hysterectomy can be done prophylactically to prevent obstetric haemorrhage as in cases of morbidly adherent placenta, it can be done as treatment in cases of uncontrollable haemorrhage from uterine rupture and uterine atony.9 Other indications include; uncontrollable bleeding from cervical laceration, invasive cervical cancer in pregnancy, post-partum uterine infections.9

Emergency peripartum hysterectomy, though lifesaving is not without its own complications, the common complications include haemorrhage requiring transfusion, post-operative severe anaemia, wound infection, injury to the bladder and ureters. Other complications are febrile morbidity, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, acute kidney injury, bowel injury and enterocutaneous fistula, perinatal and maternal death.2,3,7,10

The study is aimed at determining the incidence, indications and complications associated with emergency peripartum hysterectomies done in Federal Medical Centre, Gusau. North-West Nigeria.

Method

This is a retrospective review of the emergency peripartum hysterectomies performed in Federal Medical Centre Gusau, Zamfara State, Nigeria, from 1st January 2015 to 31st December 2021. The sources of information were Labour and obstetric ward admission registers and theatre (operations) registers as well as case folders of all patients who had hysterectomy within the period of study. The case folders of patients were retrieved from hospital records department and relevant information was obtained using a structured data extraction format. Information extracted for analysis include age, parity, educational level, booking status, mode of delivery, indication, duration of surgery, anaesthetic method, associations such as oophorectomy, blood loss, duration of hospital stay and complications.

Data Analysis: Data obtained from patient’s folder were collated using Microsoft Excel sheet and uploaded to SPSS IBM version 26. Descriptive statistics was used for frequencies, percentages and means to present the significance of the result. The results are presented in tables and figures where appropriate.

Results

A total of 20,832 deliveries took place between January 2014 and December 2020 at the Federal Medical Centre, Gusau. Five thousand one hundred and twenty-four (24.6%) had caesarean section and 15,708 (75.4%) had vaginal delivery. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy was performed in 46 cases giving a frequency of 2.2 per 1,000 deliveries. Six (13.0%), 9(19.6%), and 31(67.4%) of the hysterectomies were performed following vaginal delivery, caesarean section and emergency laparotomy for uterine rupture respectively.

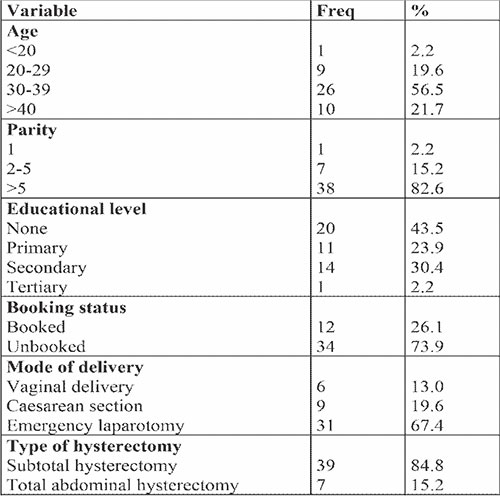

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristic of the patients

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the patients. The patients’ ages ranged from 17-44 and the mean age was 34.6 ± 6.2 years. The rate of emergency peripartum hysterectomy increased with increasing maternal age, with four-fifth of the patients being thirty years old or older. The majority of the patients were grandmultipara with the mean parity being 7.8 ± 2.7. Approximately two-third of the patients had either no education (43.5%) or primary level of education (23.9%). Only 1 (2.2%) patient had tertiary level of education. Twelve (26.1%) patients were booked and 34 (73.9%) patients were unbooked. Thirty-nine (84.8%) and 7 (15.2%) of the patients had subtotal hysterectomy and total hysterectomy respectively. Total hysterectomy was done mostly for patients with placenta previa, placenta accrete spectrum and in patient where subtotal hysterectomy failed to control the haemorrhage and the cervix had to be removed to maintain haemostasis.

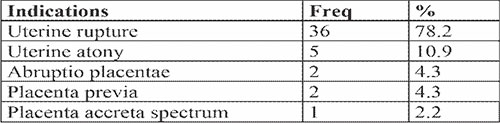

Uterine rupture was the commonest indication for peripartum hysterectomy occurring in 36 (78.2%) of the cases, followed by primary post-partum haemorrhage from uterine atony 5 (10.9%). Others included; abruptio placentae, placenta previa and placenta accreta spectrum at 4.3%. 4.3% and 2.2% respectively. Table 2.

Table 2: Indications for hysterectomy

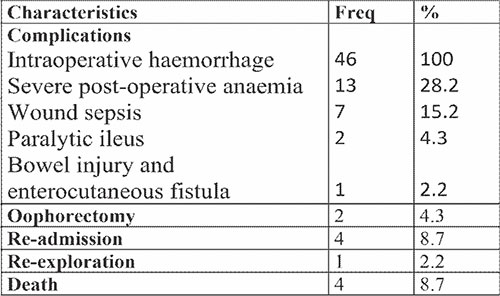

One hundred percent of the patients had intraoperative blood transfusion as a result of intraoperative haemorrhage, the mean blood loss during surgery was 1430.5 ± 2229.9mls. The complications following the procedure included severe anaemia requiring further blood transfusion in 13 (28.3%) of the patients. The mean units of blood transfused was 2.95 ± 2.04 units. Other complications included deep surgical site infection, paralytic ileus and enterocutaneous fistula occurring in 15.2%, 4.3% and 2.2% respectively.

Two (4.3%) of the patients had unilateral oophorectomy alongside the hysterectomy on account of compromise to the blood supply and non-viability of one of the ovaries. Four (8.7%) patients were re-admitted, 1 (2.2%) had re-exploration for intra-abdominal abscess drainage and maternal death occurred in 4 (8.7%) of the cases. Table 3.

Table 3: Complications and other associations with emergency peripartum hysterectomy

Discussion

Emergency peripartum hysterectomy is a life-saving procedure performed as the last resort when there are no other alternatives to control an obstetric haemorrhage thus preventing further maternal morbidity and/or mortality. We found that the incidence of emergency peripartum hysterectomy is 0.22% (2.2 per thousand deliveries). A similar finding of 0.2% and 0.26% were noted in Akwa-Ibom6 and Ekiti11 states respectively, states from the southern part of Nigeria. Higher figures have been quoted by some other Nigerian authors; Oguejiofor et al, Obiechina et al and Nwobodo et al.7,8,12 A meta-analysis that evaluated 14,409 peripartum hysterectomies from 154 studies found that the incidence of EPH in lower middle-income countries was 3 per 1,000 deliveries.13 The reason lower incidence from our study might be as a result of aversion.

Risk factors for emergency peripartum hysterectomy include; advanced maternal age, high parity, abnormal placentation in our study.13,14 In our study, we observed that most of the patients were multiparous (97.8%), the mean parity and age was approximately 7 and 34 years respectively. Similar findings have been confirmed by other studies.7,15

Uterine rupture was observed to be the most common indication for EPH in the study (78.2%), this is followed by uterine atony. This is similar to other studies from lower middle-income countries,6,7,8,11,12,16 an Ethiopian study found an incidence of 60%.17 This is however in contrast to studies done in developed countries where placental pathology was found to be the most common indication.13 This reason for difference in the most common indication for EPH between high and low income countries might be as a result of the growing rate of caesarean sections in high income countries with resultant rise in placenta previa and placenta accreta spectrum and high parity, inadequately monitored birth, injudicious use of oxytocics and false cultural and religious beliefs in low income countries.6,7,10,13

We observed that Subtotal abdominal hysterectomy (84.8%) was the most commonly performed surgical procedure in our facility and similar finding has been noted in other studies.6,7,16 This is most likely because the commonest indication for the hysterectomy in our study was uterine rupture and subtotal hysterectomy is probably safer for acutely ill patients, quicker to perform and have lesser chances of injury to adjoining structures. However, in studies where abnormal placentation was found to be the commonest indication for peripartum hysterectomy, total hysterectomy has been preferred over subtotal hysterectomy.17,18 It has been said that the best course of action in cases with placenta praevia is a total abdominal hysterectomy as it removes the placental bed in the lower uterine tract.18

EPH is done as the last resort to control obstetric haemorrhage, hence it is associated with extensive blood loss and in blood transfusion. The mean estimated blood loss intraoperatively was 1,430mls ranging from 700mls to 8,500mls and all the patients had blood transfusion with the mean units of blood transfused being 2.95 units. A study by Gica et al found the mean blood loss to be 2,200mls.19 Another study found the mean blood loss to be 2210mls and the mean blood transfusion was 4 units of blood.20 The lower estimated intraoperative blood loss might be as a result prompt decision making as most of the EPH in our study was done following emergency laparotomy for an already diagnosed ruptured uterus rather than the decision being taken intraoperatively after other measures of controlling haemorrhage has failed, especially in cases of placenta accreta spectrum disorder and uterine atony as seen in study by Gica et al.19

Documented complications associated with EPH include severe anaemia, febrile morbidity, wound sepsis, injury to adjoining structures such as the ureters, bladder and the bowel.6-8,12,13,16 In our review, we found that intraoperative blood transfusion, severe post-operative anaemia and wound sepsis were the commonest complication of the procedure.

The fatality rate in our study was 8.7%. This is similar to the finding of Jagun et al in the South-Western part of Nigeria with a fatality rate of 8%.21 This is however lower than findings by Obiechina et al8, Abasiattai et al6 and Oguejiofor et al7 that found a maternal mortality rate of 31%, 14.3% and 12.9% respectively. The older studies have a higher fatality rate and that may be explained by the better health seeking behaviour of patients, better obstetric care, blood transfusion services, anaesthetic care and the overall reduction in maternal mortality in the country in recent years.21,22

Conclusion

The incidence of emergency peripartum hysterectomy is relatively low in our study. EPH, though a lifesaving procedure, must be done with all sense of responsibility by the managing obstetrician as it has considerable impact on the life of the woman especially in relation to her future reproductive options. Its major indications are uterine rupture, uterine atony, and abnormal placentation. It is associated with significant morbidity and mortality; hence, every obstetrician should work closely with other specialists in a multidisciplinary team to reduce the complications associated with the procedure.

References

- Flood KM, Said S, Geary M, Robson M, Fitzpatrick C, Malone FD. Changing trends in peripartum hysterectomy over the last 4 decades. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2009 Jun 1;200(6):632-e1.

- Bodelon C, Bernabe-Ortiz A, Schiff MA, Reed SD. Factors associated with peripartum hysterectomy. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2009 Jul;114(1):115.

- Colmorn LB, Petersen KB, Jakobsson M, Lindqvist PG, Klungsoyr K, Källen K, Bjarnadottir RI, Tapper AM, Børdahl PE, Gottvall K, Thurn L. The Nordic Obstetric Surveillance Study: a study of complete uterine rupture, abnormally invasive placenta, peripartum hysterectomy, and severe blood loss at delivery. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2015 Jul;94(7):734-44.

- Ferreira Carvalho J, Cubal A, Torres S, Costa F, Carmo O do. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy:A 10-Year Review. ISRN Emerg Med. 2012:01–07

- Chawla J, Arora CD, Paul M, Ajmani SN. Emergency obstetric hysterectomy:a retrospective study from a teaching hospital in north india over eight years. Oman Med J. 2015;30(3):181–86.

- Abasiattai AM, Umoiyoho AJ, Utuk NM, Inyang-Etoh EC, Asuquo EP. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy in a tertiary hospital in southern Nigeria. Pan African Medical Journal. 2013;15(1).

- Oguejiofor CB, Eleje GU, Okafor OC, Okafor CG, Nkesi JC. A Ten-year Review of Emergency Peripartum Hysterectomy in Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teach-ing Hospital (NAUTH), Nnewi. Journal of Gynecology Obstetrics and Mother Health 1 (1), 01. 2023;6.

- Obiechina NJ, Eleje GU, Ezebialu IU, Okeke CA, Mbamara SU. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy in Nnewi, Nigeria: a 10-year review. Nigerian journal of clinical practice. 2012;15(2):168-71.

- Tahmina S, Daniel M, Gunasegaran P. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: A 14-year experience at a tertiary care centre in India. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research: JCDR. 2017 Sep;11(9):QC08.

- Van Den Akker T, Brobbel C, Dekkers OM, Bloemenkamp KW. Prevalence, indications, risk indicators, and outcomes of emergency peripartum hysterectomy worldwide. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2016 Dec 1;128(6):1281-94.

- Akintayo AA, Olagbuji BN, Aderoba AK, Akadiri O, Olofinbiyi BA, Bakare B. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: a multicenter study of incidence, indications and outcomes in southwestern Nigeria. Maternal and child health journal. 2016 Jun;20:1230-6.

- Nwobodo EI, Nnadi DC. Emergency obstetric hysterectomy in a tertiary hospital in sokoto, Nigeria. Annals of medical and health sciences research. 2012;2(1):37-40.

- Kallianidis AF, Rijntjes D, Brobbel C, Dekkers OM, Bloemenkamp KW, Van Den Akker T. Incidence, indications, risk factors, and outcomes of emergency peripartum hysterectomy worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2022 May 5:10-97.

- Huque S, Roberts I, Fawole B, Chaudhri R, Arulkumaran S, Shakur-Still H. Risk factors for peripartum hysterectomy among women with postpartum haemorrhage: analysis of data from the WOMAN trial. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2018 Dec;18:1-8.

- Gülücü S, Uzun KE, Ozsoy AZ, Delibasi IB. Retrospective evaluation of peripartum hysterectomy patients: 8 years' experience of tertiary health care. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice. 2022 Apr 1;25(4):483-9.

- Alabrah PW, Abasi IJ, Porbeni-Fumudoh BO, Afolabi AS, Njoku C, Wagio J. Obstetric Hysterectomy In A Tertiary Centre In Southern Nigeria.

- Bayable M, Gudu W, Wondafrash M, Sium AF. Incidence, indications, and maternal outcomes of emergency peripartum hysterectomy at a tertiary hospital in Ethiopia: A retrospective review. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2023 Apr;161(1):279-82.

- Baheti SS, AVerma MS. Emergency Obstetric Hysterectomy, Risk Factors, Indications and Outcome: A Retrospective Two Year Study. Int J Cur Res Rev. 2017 Sep;9(17):41-4.

- Gică N, Ragea C, Botezatu R, Peltecu G, Gică C, Panaitescu AM. Incidence of emergency peripartum hysterectomy in a tertiary Obstetrics Unit in Romania. Medicina. 2022 Jan 12;58(1):111.

- Qatawneh A, Fram K, Thikerallah F, Mhidat N, Fram F, Fram R, Darwish T, Abdallat T. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy at Jordan University hospital–a teaching hospital experience. Menopause Review/Przegląd Menopauzalny. 2020 Jul 13;19(2):66-71.

- Obiechina NJ, Okolie VE, Okechukwu ZC, Oguejiofor CF, Udegbunam OI, Nwajiaku LS, Ogbuokiri C, Egeonu R. Maternal mortality at Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital, Southeast Nigeria: a 10-year review (2003–2012). International Journal of Women's Health. 2013 Jul 23:431-6.

- Obeagu EI. An update on utilization of antenatal care among pregnant Women in Nigeria. Int. J. Curr. Res. Chem. Pharm. Sci. 2022;9(9):21-6.