Prevalence, pattern and factors associated with workplace violence against healthcare workers in Nigeria: A systematic review

Afolabi AA1,2, Ilesanmi OS3, Chirico F4

Abstract

Context: Workplace violence (WPV) against healthcare workers (HCWs) is mostly endured, underreported, or neglected in Nigeria.

Objective: This study aimed to describe the prevalence, pattern, and predictors of WPV against HCWs in Nigeria.

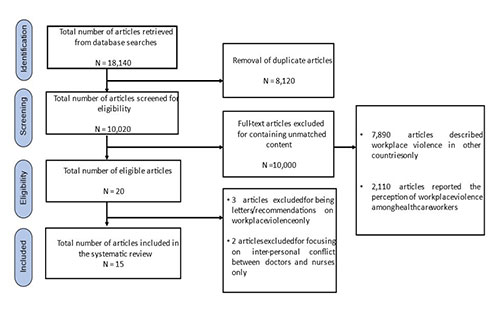

Methods: A systematic review was conducted using pre-defined keywords. The review was performed in line with the PRISMA guidelines on PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science. The population, intervention, comparator, and outcome (PICO) elements for this study were as follows: Population: Nigerian Healthcare workers; Intervention: Exposure to WPV; Comparator: Non-exposure to WPV; Outcome: Mental and Physical health outcomes of exposure to WPV. Of the 18,140 articles retrieved, 15 cross-sectional studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. In all, 3,245 HCWs were included, and consisted majorly of nurses and doctors.

Results: The overall prevalence of WPV (Physical > Verbal/Psychological > Sexual) against HCWs ranged between 39.1%-100%. The predictors of WPV are younger ages (AOR = 2.513, p = 0.012), working in psychiatric unit (AOR = 11.182, p = 0.006), and increased frequency of interaction with patients, and mostly perpetrated by patients and their relatives. Many health facilities lacked a formal reporting system and policies to protect HCWs from WPV.

Conclusion: WPV against HCWs is a public health problem in Nigeria with dire implications on HCWs; the victims, and the aggressor. Administrators of health facilities should design protocols for WPV reporting, recognition, and management. Patient and 'relatives' education on the 'facilities' policy against WPV should be undertaken, while orientation sessions on the risk factors for HCWs are scheduled.

Keywords: Healthcare workers, Workplace violence, Occupational risk, Occupational health, Nigeria

Introduction

Workplace violence (WPV) has been defined by the International Labour Organization as an array of cruel acts perpetrated in workplaces. These include homicide, verbal abuse, physical assault, bullying, sexual harassment, and psychological stress.1,2 WPV is defined by the US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health as "violent acts, including physical attacks, intended against a person at work or on duty".3 Violence exists in many workplaces, but doctors and nurses are often on the frontline of healthcare and have the most direct contact with patients and their families.4,5 There exists increasing evidence of WPV against different cadres of HCWs. Thus, WPV is now considered a major occupational hazard, especially in the healthcare sector across many continents, including Africa.5-7 In most African countries, the regulations on the safety and health of workers do not include psychosocial risks and occupational violence among those that the employer must prevent.8 The main piece of legislation regulating employment relations in Nigeria is the Labour Act. Its use is restricted to workers employed in the private and public sectors under a contract for manual labor or office work.9

Inadequate human resources for health are a serious problem in most African countries is one of the leading contributors to the continent's poor health indices.10,11 These human resource issues have been connected to underfunding in the healthcare system, loss of job satisfaction, WPV, and retention.12 For example, Nigeria has just 0.38 physicians per 1,000 patients and 1.5 nurses per 1,000 population compared to the WHO standard of 2.28 HCWs per 1,000 population.13,14 Unfortunately, a higher proportion of Nigerian HCWs has migrated to developed countries in search of greener pastures.15 The remaining few are increasingly exposed to WPV, which could motivate their unintended exit from the healthcare system.16

WPV is a worrisome phenomenon in the Nigerian health system, where it is mainly endured, underreported, or neglected.17 A study conducted in a psychiatric hospital reported that nearly 50% of mental health professionals had been physically assaulted at least once in the psychiatric facility WPV events puts a lot of strain on the institution and its employees and raises the likelihood of an occupational hazard.17,18 In Nigeria, the perceived disparity in media coverage of violent treatment of patients versus WPV against HCWs further favours patients and other perpetrators of WPV, leaving HCWs, often at the receiving end, at a complete loss.18

To the best of our knowledge, most studies conducted in Nigeria have focused more on patients. In contrast, only a few literature have described the safety of HCWs. Suppose the paucity of literature on WPV against HCWs continues, healthcare providers will continually experience this occupational hazards. A study of this nature is particularly important to increase the knowledge of WPV against HCWs and propose strategies to combat this undesirable trend. This study therefore aimed to describe the prevalence and pattern of WPV against HCWs in Nigeria, as well as the factors associated with WPV in Nigerian healthcare settings.

Methods

Study design, sample and setting: This was a systematic review of literature conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines.19

Population, Intervention, Comparator, and Outcome elements: The population, intervention, comparator, and outcome elements for this study were as follows:

Population: Nigerian Healthcare workers; Intervention: Exposure to WPV; Comparator: Non-exposure to WPV; Outcome: Mental and Physical health outcomes of exposure to WPV.

Search strategy: A systematic literature search was conducted on four namely: PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science. Thus, the possibility of missing any relevant article on the subject matter of WPV among HCWs was significantly reduced. The literature search was initially conducted between June and August 2022 and repeated between September and November 2022 to ensure that all published articles have been retrieved. All studies reporting WPV episodes against Nigerian HCWs were included in this search. Articles that did not consider Nigerian workers, considered other categories of workers other than healthcare, did not contain original observations (reviews, meta-analyses, commentaries), or considered the perception of risk but did not measure the phenomena were excluded. Table 1 shows the search string and the yield obtained at each level of the literature search. The reference lists of eligible articles were also checked to ensure adequate reporting of WPV among HCWs in Nigeria. Only literature published in English and reporting WPV against one or more cadres of HCWs was included.

Table 1: Search string employed for the systematic review of the literature

Literature search: Two authors (OSI and AAA) independently conducted the literature search and compared the retrieved results. In situations where OSI and AAA could not reach a consensus to include an article, FC intervened and provided guidance.

Data extraction process: The retrieved results from the literature search were extracted into Microsoft Excel. Data extracted included the article's citation, study location, data collection instrument, cadre of HCWs, type of WPV, causes of WPV, perpetrators of WPV, determinants of WPV, and presence of organizational policies guarding against the perpetration of WPV against HCWs. Figure 1 shows the flowchart describing the article selection strategy.

Figure 1: PRISMA flowchart showing the article selection strategy

Quality appraisal: Quality appraisal for the articles included in this review was done using the critical appraisal tool for cross-sectional studies.20 Criteria employed were based on the specificity of the study objectives, appropriateness of study design, justification of sample size, clear definition of the study population, representativeness of the study sample, description of the selection process, categorization of non-responders, appropriateness of outcome variables to the study aims, correct measurement of outcome variables using standard instruments, clear statement on the level of statistical significance, sufficiency of statistical methods to ensure repeatability, adequate description of basic data, response rate, description of non-respondents, internal consistency of the results, presented of results whose analyses were described in the methods section, justification of the results in the discussion, explanations of the limitations of the study, statements on conflicts of interests, and receipt of ethical approval. Each question had a maximum score of "1" for”Yes” and "0” for "No”. A total quality score of 20 was obtainable for each article. Each article was scored by two authors (AAA and OSI) using the twenty elements of the quality assessment tool.

Results

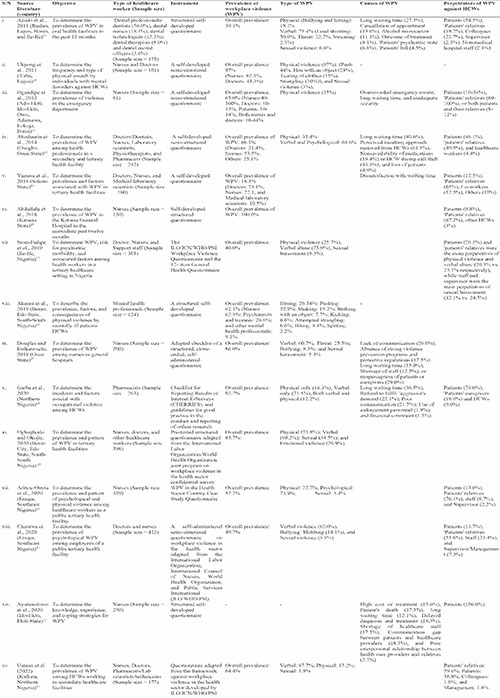

Overview: The instrument used for measuring WPV varied: Some articles used the ILO/ICN/WHO/PSI WPV, while others used a self-developed WPV questionnaire. Not all studies included used the same definition of WPV. Some articles listed only physical attacks, others verbal ones. Not all included articles considered sexual assault. Some studies considered only violence perpetrated by patients or visitors against staff. Furthermore, the retrospective period varied: in some studies, violence was investigated in the last year, in others over the entire working life. These differences make it difficult to estimate an average prevalence. Table 2 shows the summary of data extracted from each included article. Overall, 15 cross-sectional articles were retrieved on WPV against HCWs in Nigeria. Five studies were conducted in the Southwest, four in Northern Nigeria, two were conducted in the South-South, two were conducted in the Southeast, and the remaining two were conducted in multiple geopolitical zones. In all, 3,245 HCWs were included in the studies, and this study population consisted majorly of nurses and doctors. Other cadres of HCWs studied included dental technologists, dental record officers, dental therapists, laboratory scientists, physiotherapists, pharmacists, and other support staff.

Table 2: Summary of articles retrieved from the systematic review

Azodo et al. reported that 18.2% of dental professionals had been bullied and hit, 75.4% had been exposed to verbal violence, and 6.8% had been exposed to sexual violence. Long waiting time, cancellation of appointment, alcohol intoxication,patients' psychiatric state, and treatment outcome were the causes of WPV perpetrated against HCWs by patients themselves, 'patients' relatives, and senior members of the healthcare team.21 In their study, Ogundipe and colleagues reported that 65% of nurses had been physically abused either by patients and/or 'patients' relatives due to crowded emergency rooms, long waiting time, and inadequate security.22 At the Katsina General Hospital, Abdullahi and his team (2018) reported that almost 97% of nurses had been exposed to WPV meted primarily by 'patients' relatives (87.2%), and patients (9.8%).25 Using the ILO/ICN/WHO/PSI WPV Questionnaire and the 12-item General Health Questionnaire at Ile-Ife, it was reported that four of every 10 HCWs had experienced physical and verbal abuse from patients and their relatives. Sexual harassment was inflicted by staff and supervisors at work.17

The overall prevalence of WPV among nurses in general hospitals in Osun State was found to be 66%, with the majority being exposed to verbal violence. Misperceptions of patients or caregivers, lack of communication, and absence of solid violence prevention programs and protective regulations were the drivers of WPV.27

Use of formal reporting system in the organization

Overall, 24.8% of WPV cases were reported in the study by Arinze‑Onyia et al.30 Help from professional bodies was obtained in 3.1% of cases of verbal violence, bullying (14.8%), and sexual violence (14.3%).30 In the study by Chinawa and colleagues, 87.7% of WPV cases were reported either to a senior (75.4%), or to the professional union (9.2%).31 In comparison, 37.0% reported the incident through their organizational heads.27 In the cross-sectional study in Osogbo, Osun State, 9.7% of victims reported the assault to the management, 38.9% requested the services of the hospital security officials, and 68.1% sought the intervention of respective professional bodies.23 In a multi-centre national survey, 48.6% WPV victims reported the incident to superior personnel, 7.6% reported to a superior co-worker, 87.4% reported to the head of department/unit/management, while 18 (6.8%) reported the WPV incident to the police.28 In Kaduna State however, action was not taken for 80.7% of WPV cases either because the victims felt the violent act was not serious enough (91.3%) or for fear of repercussion on the victim (2.2%), or because the perpetrator apologized (6.5%), or for lack of information on the reporting system (2.2%).33 Usman et al. reported that no HCW had received any training on handling WPV.33

Only two studies documented the availability and use of a formal reporting system in healthcare facilities; the incident form was completed in 1.6% of cases of WPV in the cross-sectional study by Arinze‑Onyia and colleagues, and 3.1% of WPV cases in Chinawa and colleagues both in Enugu, Southeast Nigeria.30,31

Availability of policies to protect healthcare workers

Only one study reported the availability of policies to protect HCWs against WPV.24

Consequences of workplace violence on healthcare workers

From the findings of Azodo et al., 56.0% of incidents of WPV resulted in psychological problems among HCWs, 28.0% of WPV events impaired HCWs' job performance, while 16.0% of WPV events led to HCWs' absenteeism from work.21

Consequences for the aggressor

In instances where WPV was reported, action was taken in 105 (39.9%) events, and 75 (28.5%) of the aggrieved respondents disclosed that they were satisfied with the action(s) taken.28 In other situations where victims' satisfaction with actions taken against the aggressor was not reported, different measures were adopted, including issuance of verbal warning and discontinuance of care.30,31 In other instances, the culprit was handed to the police (11.9%) and prosecuted (2.4%).30,31

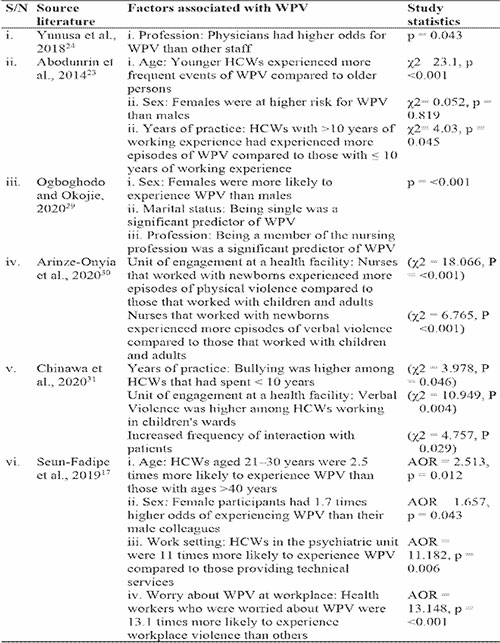

Table 3: Factors associated with workplace violence among health workers in Nigeria

Overall, seven studies described the factors associated with WPV among HCWs in Nigeria. Females were found to be at a higher risk for WPV in nearly all studies compared to males, and cadre-wise, nurses were consistently found to be at a higher risk for WPV. Age differences was reported, with younger HCWs experiencing more WPV than older HCWs in some instances (AOR=1.657),23 while working in the psychiatric ward increased HCWs' exposure to WPV by 11 folds17 (Table 3).

Quality appraisal

Overall, nine (60.0%) of the included articles had good quality, with scores ranging between 16-1817,21-24,28,30,31,33, and five (33.3%) articles had moderate quality, with scores ranging between 13-15.18,26,27,29,32 In comparison, only one (6.7%) article had low quality.25

Discussion

From this study, the prevalence of WPV against HCWs ranged between 39.1%-100%. It is, therefore, apparent that WPV is of concern in healthcare settings. The WPV rates recorded in this study are higher than the proportion of HCWs reported by the World Health Organization to be exposed to WPV at their places of primary assignment within the health facility.34 From this study, we identified that a high prevalence of physical and verbal violence among HCWs compared to other types of WPV. Other studies conducted among HCWs in North-west Ethiopia (60.2%), DR Congo (53.6%), USA (49.8%), and Malawi (22%) have reported high physical WPV rates.35-38 In addition, WPV has been reported among HCWs in the United States and other countries, accounting for nearly two-thirds of all non-fatal workplace injuries and illnesses among HCWs.39-41 Nearly all cases of WPV against HCWs take place within healthcare settings, thus indicating that interventions are expected to be initiated within the workplace environment to protect the lives of HCWs who have sworn to uphold the integrity of providing quality care to their patients against all odds. An overarching ‘'societal level’' for the socio-ecological model has been suggested as needful40-43 given that there exists a solid societal component to WPV.

We found that nurses are more exposed to WPV than other cadres of HCWs. Due to the nature of their jobs and the peculiarities of their workplaces, nurses are particularly vulnerable to WPV. There is an elevated danger due to WPV when providing care for patients during their most vulnerable moments.43 Similarly, HCWs with less professional experience were found to be at high risk for WPV. Senior members of the healthcare team have likely developed strategies to handle WPV without being seriously affected by its consequences. Given that WPV incidents may not be ruled out entirely from a healthcare facility, self-designed interventions for handling WPV should be encouraged. In like manner, organizational strategies for creating a safe working environment for nurses and other HCWs should be implemented.

Patients and their relatives/escorts were described as the primary sources of violence, which is consistent with much earlier research conducted in Ghana, Egypt, Palestine, Turkey, and Iraq.44-48 Our finding is like the research findings from Jordanian hospitals that reported patients and their relatives as the primary perpetrators of violence.49 As the main factors prompting aggressiveness from patients and their relatives, this study identified a communication gap between patients and relatives, and nurses, poor interpersonal relationships between HCWs and 'patients' relatives, delays in services owing to understaffing, and a shortage of drugs and supplies. To keep HCWs safe from aggression and its consequences, a stock-up of drugs and supplies needs to be done. Understaffing problems need to be immediately addressed, while human relationship training sessions should be organized for HCWs to interact gracefully with patients and patients' relatives.

This review identified that working in neonatal and psychiatric departments posed the most significant risk for WPV to HCWs. The results of this study are similar to reports of studies conducted in Italy and South Ethiopia where HCWs working in high tension zones such as the emergency and psychiatric department are at a high risk of exposure to WPV.50-53 This posits that a lack of self-control among psychiatric patients, non-satisfaction with 'relatives' health states, and non-certainty about the management outcome of patients being managed in psychiatric and neonatal wards are likely to pose occupational hazards to HCWs. Therefore, these zones should be mounted with suitable security measures, while HCWs posted there are sensitized early enough.

The consequences of WPV are numerous and harmful to both the victim (HCWs) and the perpetrator, that is, patients and their relatives. HCWs' psychological states could be negatively affected, causing depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and anxiety. In addition, job performance declines, which is likely to reduce patients access to quality and timely care. Emotional exhaustion and depersonalization rates were high among HCWs in Lebanon, while the rate of psychological distress was high in Palestine.54,55 This provides evidence that both the perpetrator(s) and victim(s) suffer dire consequences of WPV. To forestall such occurrences, a formal system for caregivers to report their non-satisfaction with HCWs or the type and quality of care provided for their loved one(s).

We identified the lack of WPV policies as one possible factor promoting this grave act's perpetration. Due to this current lack, a formal channel for reporting acts of WPV is absent, alongside documented stipulated punishment for the offender(s). Thus, many WPV incidents go unreported, leaving the violent person feeling justified for his action and leaving HCWs continually vulnerable to experiencing Vvolence at their workstations. Numerous interventions have been suggested in the literature, from zero-tolerance policies to talking to violent offender. In other instances, prosecution of the aggressor has also served as a deterrent to others. However, there exists no proof that this action reduces WPV against HCWs.56 Rather than declaring their stand against WPV against HCWs, many healthcare facilities design programs that concentrate on handling them.

Conclusion

Based on the results of this study, WPV against HCWs is a public health problem in Nigeria with dire implications for HCWs; the victims, the aggressor; the patient and patients' relatives. Working in high-tension zones, such as the psychiatric or neonatal wards, being females, and lack of organizational WPV policies and reporting system are major drivers of WPV against HCWs. These findings demonstrate the necessity of creating protocols for WPV reporting, recognition, management, and strategy formulation, as well as the use of additional problem-solving techniques. To identify hazards, develop interventions, and decrease such incidences, hospital administration must address the crucial problem of underreporting. The orientation sessions for HCWs should include a crucial component of education on the risk factors for WPV. These techniques may make healthcare staff more effective while at work, enhancing the quality of the services they provide. Education of patients and their relatives in handling issues that could lead to an assault on HCWs should be considered by the management of healthcare facilities in Nigeria.

Limitations

The limitations of this study essentially derive from the initial investigations. The researchers referred to non-homogeneous definitions of violence, and periods ranging from one month to the whole working life, using non-validated self-constructed questionnaires for data collection. The samples examined were always relatively small, and the authors did not always indicate the criteria they had adopted for selecting the participants. All these conditions prevented us from performing a meta-analysis and, therefore, an estimation of the average rates of violence in healthcare settings in Nigeria. Furthermore, the studies are all cross-sectional and this prevents not only a causal evaluation of the associations found between violence and effects for health and work capacity, but also an understanding. Due to the perceived minimal effect of many WPV events, and recall bias of such, the severity of WPV among HCWs may have been underestimated. But the use of unvalidated questionnaires on convenience samples does not rule out the possibility that they are overestimated, as is certainly the case for literature that have published a 100% prevalence.

This was only a systematic review of literature on WPV against HCWs in Nigeria. We acknowledge that a meta-analysis would have provided richer evidence on the subject matter.

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interest.

Funding: Not applicable

References

- International Labour Organization. Workplace Violence in the Health Sector: Country Case Studies Research Instruments Survey Questionnaire. 2003.

- Sisawo EJ, Ouédraogo SY, Huang SL. Workplace violence against nurses in the Gambia: mixed methods design. BMC Health. Serv. Res. 2017;17(1):1-1.

- US Department of Labor & Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Healthcare. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/healthcare/workplace-violence (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- Magnavita N, Heponiemi T, Chirico F. Workplace violence is associated with impaired work functioning in nurses: an Italian cross‐sectional study. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2020;52(3):281-91.

- Chirico F, Magnavita N. The crucial role of occupational health surveillance for health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Workplace Health & Safety. 2021;69(1):5-6.

- Abdellah RF, Salama KM. Prevalence and risk factors of workplace violence against health care workers in emergency department in Ismailia, Egypt. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2017;26(1):1-8.

- Chirico F, Heponiemi T, Pavlova M, Zaffina S, Magnavita N. Psychosocial risk prevention in a global occupational health perspective. A descriptive analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2019;16(14):2470.

- Abaate TJ, Inimgba T, Ogbonna VI, Onyeaghala C, Osi CU, Somiari A, et al. Workplace Violence against Health Care Workers in Nigeria. Niger. J. Med. 2022;31(6):605-10.

- Federal Republic of Nigeria. Labour Act 198. Laws of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1990.

- Okediran JO, Ilesanmi OS, Fetuga AA, Onoh I, Afolabi AA, Ogunbode O, et al. The experiences of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 crisis in Lagos, Nigeria: A qualitative study. GERMS. 2020;10(4):356.

- Oleribe OO, Momoh J, Uzochukwu BS, Mbofana F, Adebiyi A, Barbera T, et al. Identifying key challenges facing healthcare systems in Africa and potential solutions. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2019:395-403.

- Ilesanmi O, Olabumuyi O, Afolabi A. Mobilizing medical students for improved COVID-19 response in Nigeria: a stop gap in human resources for health. Global Biosecurity. 2020;2(1).

- Njaka S, Edeogu OC, Oko CC, Goni MD, Nkadi N. Work place violence (WPV) against healthcare workers in Africa: A systematic review. Heliyon. 2020;6(9):e04800.

- Chirico F, Afolabi AA, Ilesanmi OS, Nucera G, Ferrari G, Szarpak L, et al. Workplace violence against healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. J. Health. Soc. Sci. 2022;7(1):14-35.

- World Health Organization. (2016). Health workforce requirements for universal health coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals. (Human Resources for Health Observer, 17). World Health Organization. Accessed online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/250330 (accessed on 22 January 2023).

- Abubakar I, Dalglish SL, Angell B, Sanuade O, Abimbola S, Adamu AL, et al. The Lancet Nigeria Commission: investing in health and the future of the nation. Lancet. 2022;399(10330):1155-200.

- Seun-Fadipe CT, Akinsulore AA, Oginni OA. Workplace violence and risk for psychiatric morbidity among health workers in a tertiary health care setting in Nigeria: Prevalence and correlates. Psychiatry Res. 2019;272:730-6.

- Ukpong DI, Abasiubong F, Ekpo AU, Udofia O, Owoeye OA. Violence against mental health staff in Nigeria: some lessons from two mental hospitals. Nigerian Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;9(2).

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. Surg. J. 2021;88:105906.

- Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open. 2016;6(12):e011458.

- Azodo CC, Ezeja EB, Ehikhamenor EE. Occupational violence against dental professionals in southern Nigeria. African Health Sciences. 2011;11(3).

- Ogundipe KO, Etonyeaku AC, Adigun I, Ojo EO, Aladesanmi T, Taiwo JO, et al. Violence in the emergency department: a multicentre survey of nurses’ perceptions in Nigeria. Emerg. Med. 2013;30(9):758-62.

- Abodunrin OL, Adeoye OA, Adeomi AA, Akande TMM. Prevalence and forms of violence against health care professionals in a South-Western city, Nigeria. Sky Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences. 2014;2:67–72.

- Yunusa EU, Ango, UM, Musa AS, Shaba MA, Khadija AS. Health workers in tertiary hospitals in Sokoto, Nigeria. International Journal of Current Research. 2018;10:72234-72238.

- Abdullahi IH, Kochuthresiamma T, Sanusi FF. Violence against nurses in the Workplace: Who are responsible. Int J Sci Technol Manage. 2018;7:5.

- Akanni OO, Osundina AF, Olotu SO, Agbonile IO, Otakpor AN, Fela-Thomas AL. Prevalence, factors, and outcome of physical violence against mental health professionals at a Nigerian psychiatric hospital. East Asian Arch. Psychiatry. 2019;29(1):15-9.

- Douglas KE, Enikanoselu OB. Workplace violence among nurses in general hospitals in Osun State, Nigeria. Niger. J. Med. 2019;28(4):510-21.

- Garba AA, Siraj MM, Othman SH, Musa MA. A study on cybersecurity awareness among students in Yobe State University, Nigeria: A quantitative approach. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. 2020;11(5):41-9.

- Ogboghodo EO, Okojie OH. Workplace violence in the health sector: An assessment of prevalence and pattern. Eur. J. Public Health. 2020;30(Supplement_5):ckaa166-1205.

- Arinze-Onyia SU, Agwu-Umahi OR, Chinawa AT, Ndu AC, Okwor TJ, Chukukasi KW, et al. Prevalence and patterns of psychological and physical violence among nurses in a public tertiary health facility in Enugu, southeast Nigeria. Int. J. Adv. Med. Health Res. 2020;7(1):15.

- Chinawa AT, Ndu AC, Arinze-Onyia SU, Ogugua IJ, Okwor TJ, Kassy WC, et al. Prevalence of psychological workplace violence among employees of a public tertiary health facility in Enugu, Southeast Nigeria. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2020;23(1):103.

- Ayamolowo SJ, Kegbeyale RM, Ajewole KP, Adejuwon SO, Osunronbi FA, Akinyemi AO. Knowledge, Experience and Coping Strategies for Workplace Violence among Nurses in Federal Teaching Hospital, Ido-Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeria. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications. 2020:10.

- Usman NA, Dominic BE, Nwankwo BI, Nmadu AW, Omole NA, Usman OY. Violence towards health workers in the workplace: exploratory findings in secondary healthcare facilities in Kaduna metropolis, Northern Nigeria. Babcock Univ. Med. J. 2022; 5(1).

- US Bureau of Labour Statistics (USBLS) 2018. Workplace Violence In Healthcare. https://www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/cfoi/workplace-violence-healthcare-2018.htm

- Tiruneh BT, Bifftu BB, Tumebo AA, Kelkay MM, Anlay DZ, Dachew BA. Prevalence of workplace violence in Northwest Ethiopia: a multivariate analysis. BMC Nursing. 2016;15(1):1-6.

- Liu J, Gan Y, Jiang H, Li L, Dwyer R, Lu K, et al. Prevalence of workplace violence against healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019;76:927-937.

- Muzembo BA, Mbutshu LH, Ngatu NR, Malonga KF, Eitoku M, Hirota R, et al. Workplace violence towards Congolese health care workers: a survey of 436 healthcare facilities in Katanga province, Democratic Republic of Congo. J. Occup. Health. 2015;57:69-80.

- Musengamana V, Adejumo O, Banamwana G, Mukagendaneza MJ, Twahirwa TS, Munyaneza E, et al. Workplace violence experience among nurses at a selected university teaching hospital in Rwanda. Pan Afr. Me.d J. 2022;41.

- Spelten E, van Vuuren J, O’Meara P, Thomas B, Grenier M, Ferron R, et al. Workplace violence against emergency health care workers: What Strategies do Workers use?. BMC Emerg. Med. 2022;22(1):1-1.

- Pich J, Hazelton M, Sundin D, Kable A. Patient-related violence at triage: A qualitative descriptive study. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2011;19(1):12-9.

- Ramacciati N, Ceccagnoli A, Addey B. Violence against nurses in the triage area: an Italian qualitative study. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2015;23(4):274-80.

- Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The Social-Ecological Model: A Framework for Prevention. 2021. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/social-ecologicalmodel.html.

- Phillips JP. Workplace violence against health care workers in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;374(17):1661-9.

- Boafo IM, Hancock P, Gringart E. Sources, incidence and effects of non‐physical workplace violence against nurses in Ghana. Nursing Open. 2016;3(2):99-109.

- Samir N, Mohamed R, Moustafa E, Abou Saif H. Nurses' attitudes and reactions to workplace violence in obstetrics and gynaecology departments in Cairo hospitals. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2012;18 (3):198-204.

- Kitaneh M, Hamdan M. Workplace violence against physicians and nurses in Palestinian public hospitals: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012;12(1):1-9.

- Pinar R, Ucmak F. Verbal and physical violence in emergency departments: a survey of nurses in Istanbul, Turkey. J. Clin. Nurs.. 2011;20(3‐4):510-7.

- Balamurugan G, Jose TT, Nandakumar P. Patients’ violence towards nurses: A questionnaire survey. Int. J. Nurs. 2012;1(1):1-7.

- ALBashtawy M, Al-Azzam M, Rawashda A, Batiha AM, Bashaireh I, Sulaiman M. Workplace violence toward emergency department staff in Jordanian hospitals: a cross-sectional study. J. Nurs. Res. 2015;23(1):75-81.

- Ferri P, Silvestri M, Artoni C, Di Lorenzo R. Workplace violence in different settings and among various health professionals in an Italian general hospital: a cross-sectional study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2016:263-75.

- Magnavita N, Heponiemi T. Violence towards health care workers in a Public Health Care Facility in Italy: a repeated cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012;12(1):1-9.

- Magnavita N, Heponiemi T, Bevilacqua L, Capri A, Roccia K, Quaranta D, et al. Analysis of violence against health care workers through medical surveillance at the workplace in a 8-yr period. Giornale Italiano di Medicina del Lavoro ed Ergonomia. 2011;33(3 Suppl):274-7.

- Zhang J, Zheng J, Cai Y, Zheng K, Liu X. Nurses' experiences and support needs following workplace violence: A qualitative systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021;30(1-2):28-43.

- Hamdan M, Hamra A. Workplace violence towards workers in the emergency departments of Palestinian hospitals: a cross-sectional study. Hum. Resour. Health. 2015;13(1):1-9.

- Alameddine M, Mourad Y, Dimassi H. A national study on nurses’ exposure to occupational violence in Lebanon: Prevalence, consequences and associated factors. PloS One. 2015;10(9):e0137105.

- Geoffrion S, Hills DJ, Ross HM, Pich J, Hill AT, Dalsbø TK, et al. Education and training for preventing and minimizing workplace aggression directed toward healthcare workers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020(9).