Clinical validity of sonographically estimated postvoid residual volume in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia in Kano, North-West, Nigeria

Abdullahi MK1, Aji S1, Ibrahim M1, Busari AO2, Mohammed IY3*

Abstract

Background: Post-void residual urine (PVR) estimation is an important examination in patients with benign prostate hyperplasia. Urethral catheterization has been the mainstay of post-void residual urine measurement however discomfort, risk of urinary tract infection and trauma were incessantly recorded in patients. Thus, this study evaluated the accuracy of conventional ultrasound scan versus urethral catheterization for the assessment of post-void residual volume in males with benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Materials and methods: A cross-sectional study which recruited ninety-five men with benign prostatic hyperplasia at the surgical out-patient clinic of Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, Kano Nigeria. Postvoid urine volume was determined serially by ultrasound scan and after bladder emptying with urethral catheter. Data collected was analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 20.0. The reliability of postvoid ultrasound was determined using Cronbach’s reliability test while the validity was measured by calculating the test specificity, sensitivity and accuracy from a 2x2 contingency table.

Results: The age of the respondents ranged from 45 to 89 years with a mean age of 65 ± 11.4 years. Ultrasound scan was found to be 96.7% reliable in estimating residual volume with values of 141.45 ± 89.54 ml by US and of 193.54 ± 107.22 ml by urethral catheterization. The specificity, sensitivity and accuracy of ultrasound scan for estimating residual volume was found to be 100%, 80% and 60% respectively.

Conclusion: Post-void residual volume estimation by conventional ultrasound scan demonstrated reliable validity compared to urethral catheterization and can be used in a clinical setting as a noninvasive measure technique of determining post-void residual volume.

Keywords: Ultrasound Scan, Urethral Catheterization, Post-Void Residual Volume, Benign Prostate Hyperplasia.

Introduction

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a progressive disease that is characterized mainly by a deterioration of lower urinary tract symptoms over time.1 It is an age-related progressive neoplastic condition of the prostate gland.2 The occurrence might lead to serious outcomes in patients such as acute urinary retention (AUR), urinary tract infection (UTI), lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and bladder outlet obstruction (BOO).3

Clinically, BPH represents a considerable health problem for older men, due to the negative effects it has on quality of life (QOL). Globally, approximately 30 million men have symptoms related to BPH while in the United States, about 14 million men have the symptoms. BPH has a prevalence rate of 10.3%, with an incidence of 15 per 1000 men in a year, increasing with age (3 per 1000 at age 45-49 years, to 38 per 1000 at 75-79 years) whereas for a symptom free man at age 46, the risk of clinical BPH over the coming 30 years is 45%.4

The main cause of BOO in those over 40 is BPH, which can also lead to other health problems such prostatic cancer, urethral or meatal strictures, or inadequate or interrupted sphincter relaxation.2 Although urodynamic study is the most sensitive tool for BOO detection, the study requires invasive procedures and use of expensive equipment to measure the volume of residual urine in the bladder of patients presenting with LUTS which has been the traditional means of identifying patients with obstruction.1

Post-void residual Urine (PVR) is frequently the consequence of lower urinary tract dysfunction (LUTD) and BOO, while its measurement is used as parameter of efficacy for medical and surgical treatments for BPH.5 The estimation of PVR has been welcomed by Urologists from the consensus reached at the Second International Consultation on BPH.6,7 It was also suggested by Western longitudinal, population-based studies to be an important predictor of severity of LUTs in patient with BPH.8

Urethral catheterization is the gold standard technique to obtain PVR due to its accuracy and does not depend on the patient’s collaboration or extra efforts to void or empty their bladder. This technique, however, poses higher risk of urethral trauma that causes discomfort in patients which might lead to UTI even after using sterile instruments.9

The conventional ultrasonography technique visualizes the bladder directly transvaginally to give accurate measurement of low bladder volumes using the ultrasound machine's internal volume calculations or the mathematical equation.2 Although, data on the accuracy of transabdominal ultrasound for determining post-void residual is inconclusive, many studies have demonstrated high accuracy of sonographically estimated PVR.10

Since the mid 90’s, the use of ultrasonography in Nigeria has been on the increase and is widely acceptable due to its relative affordability in PVR determination. It is indispensable in emergencies, requiring no special patient preparation. In well trained hands, image display has clarity almost approaching cross sectional anatomy with no known hazards reported. Despite the benefits described above, there is little research on the utility of ultrasonographic PVR measurement hence this study aimed to determine the clinical validity of this noninvasive method of PVR assessment.

Materials and methods

Study area

The study was conducted at the Departments of Surgery and Radiology of Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital.

Study design

The study was a descriptive cross-sectional study conducted on patients who met the inclusion criteria of the study.

Ethical consideration

Ethical approval was obtained from the Hospital’s research ethical committee with reference number NHREC/28/01/2020/AKTH/EC/3053 and AKTH/MAC/SUB/12A/P-3/VI/3153 before the commencement of the study. Also, the study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Sample size determination

The minimum sample size was calculated by Fischer’s formula described by Bolarinwa.11 Using 6% prevalence of moderate to severe symptoms of LUTS in men aged 40 to 49 years,12 the minimum sample size was calculated to be 86.7 and was increased to 95 to increase the power of study.

Inclusion criteria

- Patients aged 40 years and above, newly diagnosed with BPH and consented to participate in study.

- Patients with history of persistent LUTS suggestive of BPH IPSS > 7.

Exclusion criteria

- Patients with clinical features suggestive of prostate cancer.

- Patients with difficulty in urethral catheterization.

- Patients with an indwelling bladder catheter due to acute urinary retention or neurological disorders.

- Those with neurogenic bladder.

- Those who did not consent for the study.

Sampling technique

Convenient random sampling was adopted in this study. All patients diagnosed with BPH presented through the Urology Surgical Out-Patient clinic or referred to scan room of radiology department from general outpatient department of the hospital were screened for eligibility to participate in the study; those that met the inclusion criteria and consented to participate were recruited consecutively until the desired sample size was obtained.

Study protocol

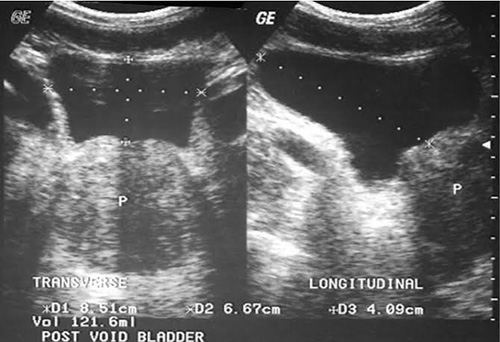

The study employed quantitative method of data collection. A registrar from Urology unit, a radiologist and a senior registrar from Radiology department were deployed to collect the patient data after duely informed them of the research protocol. All examinations were performed per abdomen , by the radiologist first, using a real time ultrasound scanner (SonoScape model SSI-8000) with a 3.5MHZ sector transducer. Each patient underwent two examinations, the first of which was with full bladder and the second immediately after voiding urine. Measurements taken include width of the bladder, its Anterior Posterior dimensions in the Transverse scan and Length of the bladder on the longitudinal scan. The measurement was then repeated by the senior registrar and average of the values obtained was recorded PVR1. The prostate volume was also measured and documented.

After the ultrasound scan estimation of the PVR, there was an insertion of size 18-F foley’s urethral catheter under aseptic technique and local anaesthesia in a dedicated room close to the scan room. The bladder was emptied into a urine collecting bag, with the endpoint of collection of residual urine defined as the cessation of flow and slow withdrawal of the catheter into the proximal urethra, and this volume was recorded as PVR2. The interval from the end of the ultrasound scan measurement and collection of residual urine was approximately 5minutes. A PVR of more the 100ml was considered significant.

Study instrument

An interviewer – administered, semi-structured questionnaire was used to collect data from eligible respondents after a pretest. The questionnaire has four sections that sought information on:

- Socio-demographic data of the respondents.

- History.

- Examination.

- Investigation.

Data management

Patient’s demographic, clinical and PVR data were collected and entered into a proforma prepared for the study. Data cleaning was done after manually checked for errors. Also, coding of questionnaires was done before data entry into the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 20. Quantitative variables were described using measures of central tendency, the quartiles and measures of dispersion. Whereas qualitative data were presented as n (%). Normality of numerical variables was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test and Q-Q plots. Wilcoxon test was used to analyze the difference between the two measurements of non-normally distributed variables. While McNemar test was used to determine whether there was difference between the grouped PVR values. P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Figure 1: PVR measurement using conventional ultrasound scan

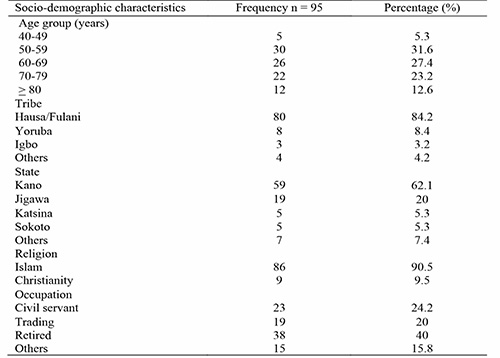

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of the study population

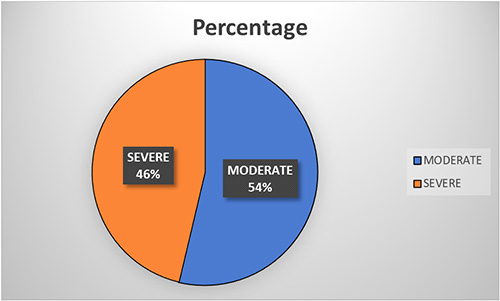

Figure 2: Distribution of the patients based on the severity of LUTS by IPSS. A 54% of the respondents have moderate IPSS

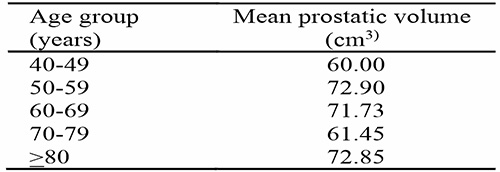

Table 2: Mean Prostatic Volume of the Respondent by Age Group Among Men with BPH

The mean prostatic volume of the respondents with BPH is 69.2 ± 17.6 which ranges from 60 to 72.9 cm3 with the largest in the age group of 50 – 59 years.

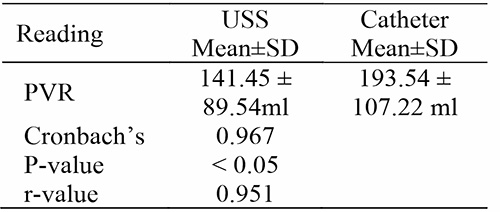

Table 3: Reliability of post-void residual volume measurement by conventional ultrasound scan among patients with BPH

Using Cronbach’s alpha, the reliability of US for measuring the PVR is 96.7% with values of 141.45±89.54 ml by US and of 193.54±107.22 ml by urethral catheterization (r = 0.951 and P < 0.05). This indicated that the test is reliable, as Cronbach’s alpha is greater than 0.7.

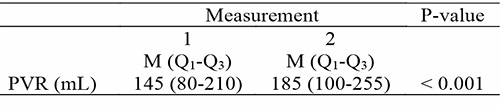

Table 4: The difference between PVR1 and PVR2

The PVR1 values were statistically lower than the PVR2 values at p < 0.001

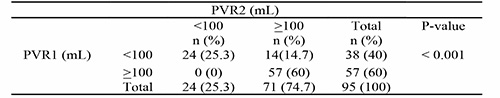

Table 5: Comparison between the grouped PVR of the patients

Specificity = 24/(0+24) = 100%

Sensitivity = 57/(14+57) = 80%

Accuracy = (57+0)/(57+0+14+24) = 60%

Conventional ultrasonography is highly (100%) specific with a sensitivity and accuracy of 80% and 60% respectively in measuring post-void residual volume.

The age of the respondents ranged from 45 to 89 years with a mean age of 65 ± 11.4 years. Majority of the respondent were between the age ranges of 50-59 years (30%). Majority (90.5%) of the participants were Muslims and of Hausa (84.2%), Yoruba (8.4%) tribes or Igbo (3.2). Other tribes (4.2%) included: Kanuri, Egbira. Most of the respondents (62.1%) were Kano indigene followed by Jigawa (20%) and others states (7.4%) included: Maiduguri, Lagos and Osun.

Discussion

A total of 95 participants that presented with BPH in the Hospital were recruited into this study after obtaining their informed consent. The mean age of the participants was 65 ± 11.4 years, with majority falling within 50-59 years age group which is consistent with findings by Amole et al. who assessed 52 consecutive patients with BPH and recorded a mean age of 64.98 ± 9.57 years.13 Also, Simforoosh et al. who studied 324 men with persistent LUTS and reported a mean age 61.5 years.14 Similarly, Abdelwahab et al. in Egypt and Toyobo from Lagos State University Teaching Hospital (LASUTH) reported mean age of 63.8 years and 65 years respectively.15,16 However, in contrary, lower mean age of 50.2 ± 20.2 years was reported by Jalbani and Ather in study conducted to determine the accuracy of three-dimensional bladder ultrasonography of residual urinary volume measurement compared with conventional catheterization which might be attributed to poor health seeking behavior of African societies where most cases presented late.17

In 1944, Swyer described the typical patterns of prostate growth in men with different patterns emerging after age 45.85 years and he specifically suggested that some men with BPH experience further increases in prostate size, while in others the size remains unchanged or the prostate atrophies with advancing age.18 Findings in this study showed that the mean prostatic volume of the respondents is 69.2 ± 17.6cm3 with the mean prostatic volume by age group ranging from 60 to 72.9cm3 with the largest in the age group of 50 – 59 years and a gradual increase with increase in the patient’s age. In agreement with our findings, Toyobo reported an increase in the volume of the prostate with increase in the age.16 Tsukamoto et al. who examined a longitudinal change in prostate volume in 67 Japanese men with LUTs reported that prostate volume increased in 46 men (70%), remained stable in 10 (15%) and decreased in 11 (15%).19

Jacobsen et al. also observed that the prostate slightly increases in size until puberty and after which there is rapid enlargement.20 This high growth rate is maintained, until the third decade. After the age of 45–50 years the prostate may either undergo benign hypertrophy so that its size increases gradually until death or it may undergo atrophy. In contrast to our findings, Tahir and Ahidjo reported a decrease in the prostatic volume after 40 years which could be attributed to the fact that their study was conducted on normal subjects with no history of prostatic disease or urinary tract symptoms.21

Our reliability testing result showed that conventional ultrasound scan estimate was found to be reliable, as Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95 (>0.7) (P < 0.05). It was also shown to be highly (100%) specific with sensitivity of 80% and accuracy of 60%. This is in agreement with Nwosu et al. who reported that conventional ultrasound scan is useful and accurate for measuring post-void residual volume, and a good correlation with the catheterization volume.22 In contrast to this Kiely et al. found that conventional ultrasound scan could provide an approximate measurement of bladder urine volume, but it was not sufficiently reliable and accurate in situations where more precise measurements of changes in PVR were required.23 Roehrborn and Peters, also showed that urethral catheterization was more accurate and reliable than conventional ultrasound scan for predicting the actual bladder urine volume however, abdominal ultrasonography is less invasive than catheterization, and can also be used to assess bladder wall thickness.24 In addition, a poor correlation between bladder volumes measured by ultrasonography and urethral catheterization, showed that ultrasonography cannot reliably and accurately measure bladder volumes, and catheterization appeared to be most accurate method of measuring PVR, especially at low values.14,25

Conclusion

Conclusively, our study showed that the mean age of the respondents was 65 ± 11.4 years and majority fall in the category of 50-59 years age group with mean prostatic volume of 69.2 ± 17.6 cm3. Also, our study observed that the use of conventional ultrasound for PVR measurement demonstrated reliability (Cronbach alpha = 96.7%), highly specificity (100%), high sensitivity (80%) and accuracy (60%) that is suggestive of reliable measurement of PVR.

Recommendations

Ultrasound scanning is a reliable, sensitive, specific, accurate and non-invasive method of estimating residual volume and is recommended routine clinical evaluation of patients with BPH.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Emberton M. Definition of at-risk patients: Dynamic variables. BJU. 2006; 97(s2):12–15.

- Ballstaedt W.B. Bladder Post-void Residual Volume. 2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539839/?report=classic.

- Xia S, Cui D, Jiang Q. An overview of prostate diseases and their characteristics specific to Asian men. Asian J Androl. 2012; 14(3):458–64.

- Denis L, McConnell J, Yoshida O. the Members of the Committees. 4th International Consultation of BPH Recommendations of the International Scientific Committee: the evaluation and treatment of lower urinary tract syndromes (LUTS) suggestive of benign prostatic obstruction In Proceedings of the 4th International Edit. 1997. p. 669–684.

- Asimakopoulos AD, Nunzio C, De Kocjancic E, et al. Measurement of post-void residual Urine. 2016; 57:55–57.

- Dudley. Clinical agreement between automated and calculated ultrasound measurement of bladder volume. British Journal of Radiology 2003; 76: 832 – 834.

- Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology in lower urinary tract function: Report from the standardisation sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Urology. 2003; 61(1):37–49.

- Beekman M, Merrick GS, Butler WM, et al. Selecting patients with pretreatment postvoid residual urine volume less than 100 ml may favorably influence brachytherapy-related urinary morbidity. Urology. 2005;66(6):1266–70.

- Alberto P. Post-void residual urine volume: an overview. Ben’s natural health. 2021;1

- Park YH, Ku JH, Oh SJ. Accuracy of post-void residual urine volume measurement using a portable ultrasound bladder scanner with real-time pre-scan imaging. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30(3):335–8.

- Bolarinwa OA. Sample size estimation for health and social science researchers: The principles and considerations for different study designs. Nigeria Postgraduate Medical Journal 2020; 27: 67-75.

- Byun SS, Kim HH, Lee E, et al. Accuracy of bladder volume determinations by ultrasonography: Are they accurate over entire bladder volume range? Urology. 2003; 62(4):656–60.

- Amole AO, Kuranga SA, Oyejola BA. Sonographic assessment of postvoid residual urine volumes in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004; 96(2 Suppl.):234–9.

- Simforoosh N, Dadkhah F, Hosseini SY, et al. Accuracy of residual urine measurement in men: Comparison between real-time ultrasonography and catheterization. J Urol. 1997;158(1):59–61.

- Abdelwahab HA, Abdalla HM, Sherief MH, Ibrahim MB, Shamaa MA. The reliability and reproducibility of ultrasonography for measuring the residual urine volume in men with lower urinary tract symptoms. Arab J Urol. 2014;12(4):285–9.

- Toyobo OO. (2006). Sonographic estimation of postvoid residual urine volume measurement in patients with prostate enlargement in Lagos university. A dissertation submitted to the National Postgraduate Medical College of Nigeria in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the fellowship in radiology.

- Jalbani IK, Ather MH. The accuracy of three-dimensional bladder ultrasonography in determining the residual urinary volume compared with conventional catheterization. Arab J Urol. 2014; c:1–6.

- Swyer GI. Post-natal growth changes in the human prostate. J Anat. 1944; 78:130.

- Tsukamoto T, Masumori N, Rahman M, et al. Change in International Prostate Symptom Score, prostrate-specific antigen and prostate volume in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia followed longitudinally. Int J Urol. 2007; 14:321.

- Jacobsen SJ, Jacobson DJ, Girman CJ, et al. Treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia among community dwelling men: The Olmsted County study of urinary symptoms and health status. J Urol. 1999;162(4):1301–6.

- Tahir A, Ahidjo A. Variation of prostatic volume with advancing age among adult Nigerians. Arch Nig Med. 2004; 1:12–14.

- Nwosu CR, Khan KS, Chien PFW, et al. Is real-time ultrasonic bladder volume estimation reliable and valid? A systematic overview. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1998;32(5):325–30.

- Kiely EA, Hartnell GG, Gibson RN, Williams G. Measurement of Bladder Volume by Real‐time Ultrasound. Br J Urol. 1987;60(1):33–5.

- Roehrborn CG, Peters PC. Uroradiology can transabdominal of postvoiding catheterization? Ultrasound Estimation (PVR) replace only one diameter of the bladder, were found to be much less accurate. For any arbitrary value of PVR, used in determining clinical management, The Urology. 1988; XxX(5):445–9.

- Alnaif B, Drutz HP. The accuracy of portable abdominal ultrasound equipment in measuring postvoid residual volume. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1999;10(4):215-8.